Quick answer: Strong OKRs are outcome-focused, limited in number, and reviewed on a consistent cadence. They work when leaders make tradeoffs visible and use reviews to decide, not just report.

Operator note: OKRs break when they turn into a long list of tasks. Fewer, outcome-based OKRs with a consistent review cadence beat perfect wording every time.

You know it's working when:

- Teams set a small number of OKRs and can explain the why behind them.

- Key Results are measurable and reviewed on a predictable rhythm.

- Initiatives connect to outcomes, and status updates include context and next actions.

In this guide:

- What “good” OKRs look like

- How to write OKRs that teams can execute

- How to run OKR reviews that drive decisions

- Common OKR mistakes

- Copy/paste template

- FAQs

What “good” OKRs look like

- Objectives are outcomes. They describe what changes, not what you will do.

- Key results are measurable. A baseline, a target, and a clear owner.

- Few enough to review. If leaders cannot review them, they will not.

If you need a dashboard structure, see OKR dashboard guide.

How to write OKRs that teams can execute

- Start with Themes. OKRs should connect to the strategic bets. Use your strategic planning process as a reference.

- Write one objective per outcome. Avoid objectives that bundle multiple outcomes together.

- Choose 2 to 4 key results. More KRs usually means unclear focus.

- Make input and output explicit. If a KR is an activity, label it honestly and add at least one outcome measure.

How to run OKR reviews that drive decisions

- Use pre-reads so meeting time is for decisions.

- Discuss risks and dependencies before they become urgent.

- Capture decisions and follow-ups, then publish them.

Most teams improve reviews by tightening cadence. The Operating Cadence Guide is a practical starting point.

Common OKR mistakes

- OKRs as task lists. Execution activity gets reported, but outcomes do not move.

- Too many objectives. The org loses focus and leaders stop reviewing.

- No linkage to strategy. Teams write OKRs, but the company priorities do not change.

Checklist: OKR setup for next quarter

- 3 to 5 Themes or top priorities

- 1 to 2 objectives per team (as a starting point)

- 2 to 4 key results per objective, with baselines and targets

- A weekly/biweekly update rhythm and a weekly or bi-weekly leadership review

External reference

Many leadership teams still use John Doerr’s OKRs Explained as a practical OKR reference point.

Once OKRs are set, the next challenge is follow-through. See strategy execution software.

Copy/paste template: OKR draft that holds up in review

Example scenario: Before the quarter starts, each team brings a draft objective with 2–3 measurable key results and a clear owner. In review, leadership tests the draft by asking: do these key results prove the objective happened, and can we update them weekly without writing essays?

Draft OKRs so leadership can approve them quickly. The goal is clarity, not clever wording.

Objective: [outcome statement that can be explained in one breath]

Key Results (2–3): [metric + baseline + target + date for each]

Owner: [single accountable owner]

Initiatives that drive the KRs: [top 3 initiatives]

Risks: [top 2 risks and mitigations]

Review cadence: weekly updates, weekly or bi-weekly leadership review

FAQs

Are OKRs only for product and engineering?

No. Any function can use OKRs when objectives describe an outcome and key results measure impact. The key is making cross-functional dependencies visible.

How many OKRs should a company have?

Start small. A few company-level priorities, then a manageable number of team OKRs aligned to them. If leaders cannot review the set monthly, it is too many.

Should OKRs be tied to compensation?

Usually not directly. When compensation is tightly linked, teams may optimize for score rather than learning and true outcomes.

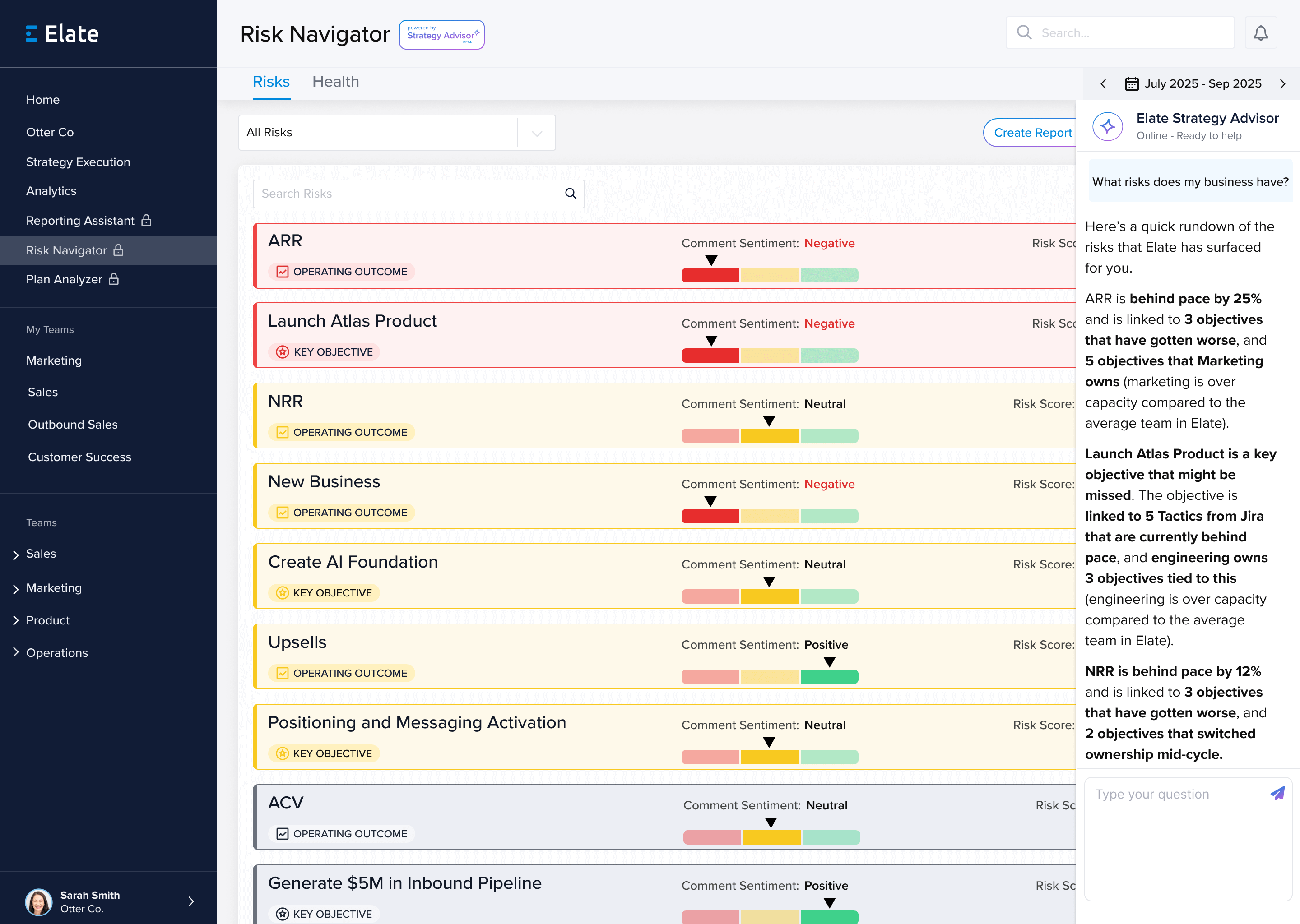

Want to make this easier to run every week? See a short Elate walkthrough, then decide if a live demo is worth your time.